What is an OS?

It’s actually kind of difficult to define what an operating system is. There are a lot of different kinds of operating systems, and they all do different kinds of things.

Some things are commonly bundled with operating systems, but are arguably not part of the essence of what makes an OS an OS. For example, many operating systems are often marketed as coming equipped with a web browser or email client. Are web browsers and email clients essential to operating systems? Many would argue the answer is no.

There are some shared goals we can find among all operating systems, however. Let’s try this out as a working definition:

An operating system is a program that provides a platform for other programs. It provides two things to these programs: abstractions and isolation.

This is good enough for now. Let’s consider this a test for inclusion, but not exclusion. In other words, things that fit this definition are operating systems, but things that don’t may or may not be, we don’t quite know.

Creating abstractions

There are many reasons to create a platform for other programs, but a common one for operating systems is to abstract over hardware.

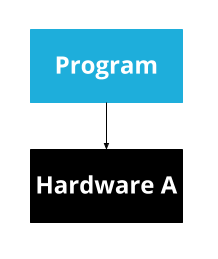

Consider a program, running on some hardware:

This program will need to know exactly about what kind of hardware exists. If you want to run it on a different computer, it will have to know exactly about that computer too. And if you want to write a second program, you’ll have to re-write a bunch of code for interacting with the hardware.

All problems in computer science can be solved by another level of indirection.

- David Wheeler

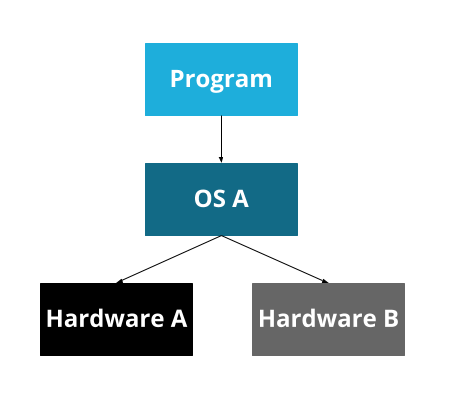

To solve this problem, we can introduce an abstraction:

Now, the operating system can handle the details of the hardware, and provide an API for it. A program can be written for that operating system’s API, and can then run on any hardware that the operating system supports.

At some point, though, we developed many operating systems. Since operating systems are platforms, most people pick one and have only that one on their computer. So now we have a problem that looks the same, but is a bit different: our program is now specific to an OS, rather than specific to a particular bit of hardware.

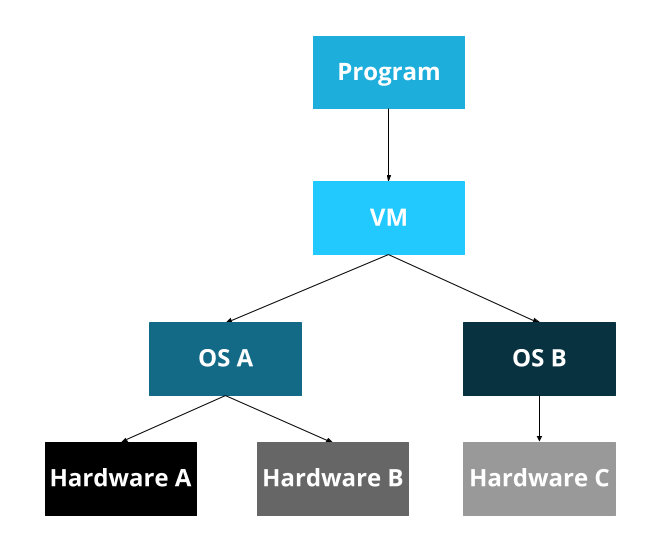

To solve this, some programming languages have a ‘virtual machine.’ This was a big selling point of Java, for example: the Java Virtual Machine. The idea here is that we create a virtual machine on top of the real machine.

Now, you write programs for the Java Virtual Machine, which is then ported to each operating system, which is then ported to all the hardware. Whew!

This, of course, leads to the corollary to the previous maxim:

...except for the problem of too many layers of indirection.

- Kevlin Henney

We now have a pattern:

- I have

A. Ais written explicitly forX...- ... but I want to support

XandY, - so I put abstraction

Bin the middle.

We will see this pattern over and over again. Hence ‘intermezzo’: abstractions are always in the middle.

Isolation

Many of the abstractions provided are, as we discussed, abstractions over hardware. And hardware often has a pretty serious restriction: only one program can access the hardware at a time. So if our operating system is going to be able to run multiple programs, which is a common feature of many operating systems, we’ll also need to make sure that multiple programs cannot access hardware at the same time.

This really applies to more than just hardware though: it also applies to shared resources (e.g. memory). Once we have two programs, it would be ideal to not let them mess with each other. Consider any sort of program that deals with your password: if programs could mess with each other’s memory and code, then a program could trivially steal your password from another program!

This is just one symptom of a general problem. It’s much better to isolate programs from each other, for a number of different reasons. For now, we’ll just consider isolation as one of our important jobs, as OS authors.

Wait a minute...

Here’s a question for you to ponder: if we didn’t provide isolation, isn’t that just a poor abstraction? In other words, if we had an abstraction where we could interact with other things being abstracted... isn’t that just a bad job of doing the abstraction? And in that sense, is the only thing an operating system does abstraction? Is the only thing everything does abstraction?

I don’t have answers for you. If you figure it out, let me know...